“Come out ye Black and Tans,” the Irish rebel song commands, in response to the occupation of Ireland by the British army and the barbarity many have suffered under British jurisdiction over the centuries. The struggle to regain their status as a republic was a long, bloody and tumultuous road.

Beginning with the Anglo-Norman invasion in the 12th century, the British Constitution oversaw the great famine of the mid-19th century, which killed more than a million people as a result of famine and the forced export of Irish produce, before the culminated in the Irish War of Independence in 1921. After the Irish Republic was established and the Land of Saints and Scholars liberated from the shackles of British rule, attention turned to Northern Ireland and the civil unrest between Loyalists and Republicans, Catholics and Protestants.

The legacy of Bobby Sands

Bobby Sands is a name that is often revered; he is to the Irish what Che Guevara is to Cubans. A revolutionary and freedom fighter, politician and poet, Sands became a political prisoner, imprisoned by the British state and the system that had historically persecuted his people. After fighting hard for the reunification of the republic and Northern Ireland, Sands led the 1981 hunger strike, which resulted in his death and subsequent martyrdom.

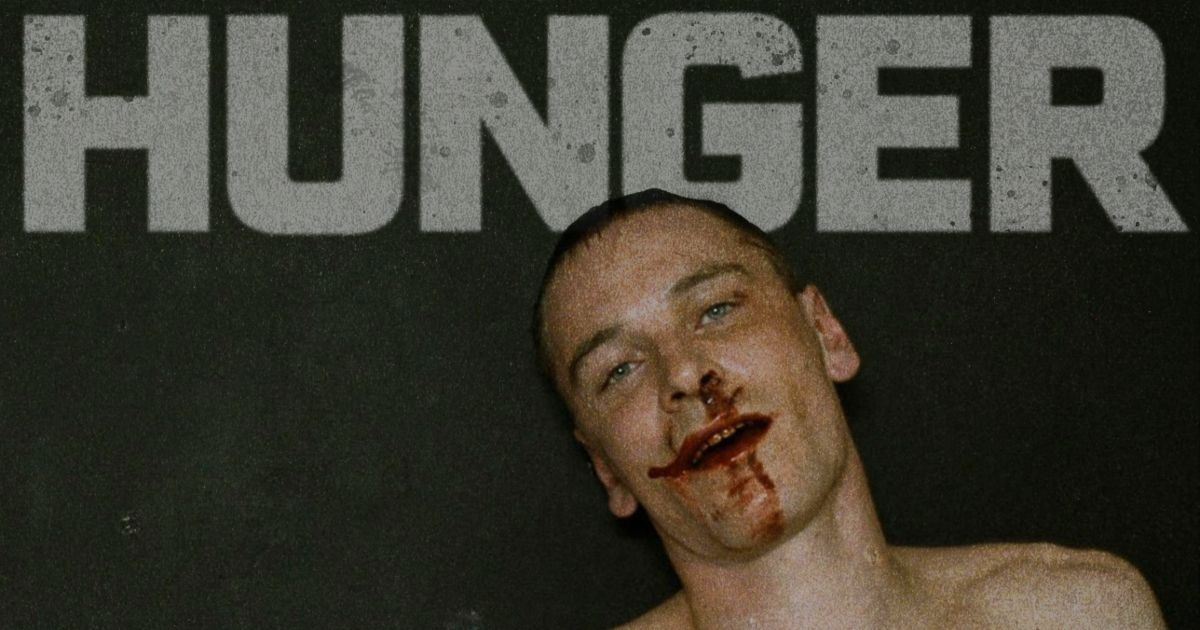

Following the recent census in Northern Ireland, for the first time in the country’s history, Catholics outnumber Protestants. It’s a statistic that certainly bolsters hopes for an independence referendum, thanks in large part to the tireless protests of Sands and men like him. In Steve McQueen’s 2008 Political Drama hunger, starring Michael Fassbender as Sands, we get an unadorned picture of the reality of the ’81 hunger strikes at Maze Prison in County Down.

Hunger tells Sands’ story in a painful way

Director Steve McQueen has a penchant for exposing the horrors of humanity and investigating the utter depravity of certain prominent historical events. From 12 years slave and Shame until small axe and hungerMcQueen rarely shuns the grim realities of life and uses extreme techniques to get his point across on screen.

hunger is a palpably harrowing story, a sensory overload that you can practically smell, touch and taste, from the human feces hung on the interior of the cell to the prolonged sound of this deafening silence that wears away at your ears as the trauma unfolds. you unfold incredulous eyes.

hunger is not a film that exists solely to offer an exploration of the treatment of political prisoners and the effort the prisoners made to protest; no, it’s a movie that also locks up his audience. It locks us up and throws away the key. We are starved, beaten, humiliated and mocked in the most undignified, grotesque way imaginable. Dragged naked through icy corridors, subjected to the brutalist regime of the prison guards and forced to endure the hardships Sands himself experienced.

Michael Fassbender pays perfect tribute to Bobby Sands

Fassbender’s illustration of Sands as a man guided by the strictest virtuosity in the face of such adversity is both compelling and terrifyingly unforgettable. With a paltry 900 calories a day in preparation for the role, the German-born and brilliantly multilingual actor underwent one of the most extreme body transformations an actor could possibly have, shedding a whopping 40 pounds. He carved a skeletal figure on the screen, and it emphasizes the level of self-torture so deeply that the real Sands had the willpower to endure.

In a film littered with symbols and iconography of the stark deterioration of the situation the hunger strikers had felt so strongly in, the most disturbing element of McQueen’s grim portrait is watching the starving Sands languish in this weak, emaciated, and malnourished shell: unresponsive and deprived of energy, he was essentially the walking death. Plates of uneaten food were placed at what would become his deathbed, in hopes that he would succumb to his own temptation. He never did.

In an act of absolute defiance and unyielding defiance, the film documents his final days as a man who was willing to abandon his own life, which was still so full of hope, to save the hopes of his people and fight for a better future, even if it meant an end to his own.

Hunger’s 17-minute shot reflects his stunning performance

hunger contains a series of sequences in its essentially three-part structure, each one more impressive than the next. But aside from Sands’ dirty protests and violent haircut, the halfway scene where Sands sits opposite Father Dominic Moran (Liam Cunningham) is arguably one of the most poignant. “A little break from smoking the Bible… you figured out which part is the best smoke?” Moran jovially says to a topless Bobby, waiting for a real cigarette after rolling so many of his own with the only paper he had.

The verbal joust between the couple in an underlit visiting room is the only real let down of the entire film. But even in the face of a man with more experience and ostensibly greater social standing, Sands somehow manages to hold the priest’s attention and even earn his amazement. The one-take scene doesn’t break from the atmospheric wide shot for an unprecedented 17 minutes until Sands begins his monologue about the dying foal and the genesis of his steadfast belief to always do the right thing.

hunger isn’t a movie you probably want to see again; you’ll never forget it anyway, so it almost seems redundant. An important film about an important man, it makes its point, it shocks you, and it is so indelible that, like the feces-stained walls in his filthy prisons, it is permanently inscribed on the walls of your memory.