As perhaps the most seminal comic book writer of the modern age, Alan Moore‘s work on the page and in the panels was inevitably going to be utilized for the big screen eventually. Moore, the English writer who found fame revolutionizing the comic book industry in the 1980s, reflects the very characters and words that he created: pulpy, brash, cutting, and cynical, but always extremely entertaining. And Moore’s universally negative comments on the films and TV shows that have come out of his works can be looked at in one of two ways:

1) These comments are coming from a hugely talented writer that has time and again been wronged by the people who originally commissioned his works and now have free rein to do with what they please. His negativity should thus be seen as representative of a bigger problem facing lots of the creatives behind the scenes in the comic industry, especially as the medium continues to boom in onscreen superhero adaptations. From a film critic’s point of view, with more misses than hits on the big screen based on his works, Moore’s views are also arguably fair in their disappointed and jaded verdicts.

Or

2) Moore is a bitter hypocrite who hasn’t seen any of the visual takes in the first place (and as such has no legitimate reason to say so sweepingly that none of them are good). From this perspective, he is so closed off to the world now that he refuses to accept that fans can (and should) take on their own interpretations of his creations, and that with time the impact Moore’s work had on the world will change as the world does. At the same time, he is more than content to appear publicly and denounce these adaptations while cashing the checks that he’s received for them (before he began refusing them, that is).

Whichever perspective one takes, Moore has undoubtedly made an impact. Below we have collected each of his thoughts on the films and series that have come from his comic books, from previous interviews throughout the years.

Swamp Thing (1982) & Return of Swamp Thing (1989)

Most notable now for being directed by Scream and Nightmare on Elm Street‘s Wes Craven, this is perhaps the first legitimate studio film from the director after a couple legendary lo-fi exploitation horror films and one botched mainstream attempt. Campy and unorthodox, Swamp Thing went on to receive middle of the road responses. Two years later Craven could improve upon his learning through a studio film with Freddy Krueger and Nightmare on Elm Street. The sequel, Return of Swamp Thing (1989), would star Heather Locklear.

The more recent TV adaption of Swamp Thing, released in 2019, offered nothing remarkable. Flat and dull, the series was canceled after its first season. In Bill Baker’s book Alan Moore’s Exit Interview, the creator summed it up:

“Now, ever since I started to do work that attracted interest from the film industry, which was pretty close to the beginning of my career, actually, I had taken a rather dim view of it. Possibly because my first exposure to having my work filmed was when they made the regrettable Return of the Swamp Thing which, due to the perhaps unwise contract that DC had signed with the producers of The Swamp Thing movie, back when DC were desperate to get any of their books filmed, the contract stated that the filmmakers were at liberty to take anything from The Swamp Thing title, from any point during the book’s past or future. That was why the second Swamp Thing film featured ideas and lines of butchered dialogue that had been taken from my comparatively thoughtful comics, making them travesties of my work, basically, which I wasn’t too happy about.”

From Hell (2001)

A fresh-faced Johnny Depp must crack the case of Jack The Ripper as he stalks Victorian London and murders prostitutes. Stylistic with its period setting and dark themes, From Hell boasts a fantastic cast all in good form in this darkly intriguing murder mystery whodunit. With a favorable reception on release, and debuting as number one at the box office on opening weekend, as far as Moore’s comments go this is one of the least vindictive. Speaking to Peter Murphy for The New Review, Moore said:

Nah, Melinda (Gebbie) went to see it and said, ‘Not a bad film.’ She found Johnny Depp’s performance a little bit tepid. She thought if they’d focused more upon Ian Holm it would’ve perhaps been a much better film. My daughters thought it was okay. Nobody said it was actually a really bad film. Iain Sinclair gave the most succinct summing up of it when he said, ‘It’s not a bad film in it own right, but it does kind of represent this American colonization of the imagination.’ Without having seen it obviously I’m talking through me hat, but that sounds like a likely accurate verdict.

I was never sure why they actually bothered to buy the rights to ‘From Hell,’ because you take away all of the ruminations upon architecture and history and mysticism and all the rest of it, you’re pretty much left with the original story done by Michael Caine, Christopher Plummer, all of these people in various productions.

Panned by everyone who saw it, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen remains one of the biggest stinkers in Hollywood history. More famed for its toxicity on set than its actual story, this is the movie that the late Sean Connery would go out of his way to help edit on, physically brawl with the director, and subsequently make him retire from acting all together.

In the same interview with New Review Moore said:

Of course, they shot ‘League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen’ with Sean Connery, and to make it more acceptable to American audiences, which is of course a prime consideration, they had Tom Sawyer as one of the cast, so I imagine there was a completely riveting picket fence painting scene shoehorned into the story at some point.

In 2016, AV Club quoted From Hell and League of Gentlemen producer Don Murphy as writing on Jeffrey Wells’ Hollywood Elsewhere website (in response to a message about Moore):

Alan Moore is a hypocrite and a liar.

– He took a million dollars from Fox for League – he did not HAVE to do so

– He claims that he never saw League, so why does he get to comment on the merits of it? YOU can say what you want to – but he never saw it

-He has made over $3 million dollars on the increased sales of the Watchmen hardcover due to the film – he isn’t returning that money

-He sold the rights to Watchmen in 1988

-He attacked V for Vendetta back when it came out – after he had sold those rights

-He is an old man who smokes too much hash and prays to a lizard god. Don’t buy his bullshit.

Constantine (2005)

Based on his Swamp Thing character, John Constantine was later given his own run of comic books in the Hellblazer series. Just before the superhero movie boom was on its way, Constantine pitched a post-Matrix Keanu Reeves as its magician-cum-occult expert in the field. With average reviews, but fantastic returns at the box office, a sequel is said to be on the way.

Published on March 3rd 2004, a mole calling themselves “Bristlehound” wrote for Aint It Cool, revealing:

After reviewing the script and casting of HELLBLAZER, Comic Kingpin Alan Moore has done the unthinkable. He’s washed his hand of the entire debacle. That’s right – he’s instructed DC to NOT credit him as the creator of the character. And putting his money where his mouth is, he has instructed that the royalties that he was splitting with his co-creators goes EXCLUSIVELY to the artists, Veitch and Bissette.

Often we hear about an artist upset that his creation has been butchered but this is the first I can recall where the creator asked that both name and money be rejected. Moore is apparently so upset at the desecration done to Constantine by Producer Lauren Shuler Donner that he is stating that he will never support a film project based on his work again.

Moore’s own comments talking to BBC Radio 4 in 2005 would seem to back Bristlehound up. Moore said:

Then I got a phone call from Karen Berger the next Monday, she’s an editor at DC Comics, and she said, “Yeah, we’re going to be sending you a huge amount of money before the end of the year because they’re making this film if your Constantine character with Keanu Reeves.” I said, “Right, OK. Well, take my name off of it and distribute my money amongst the other artists.”

I felt, well, that was difficult, but I did it and I feel pretty good about myself.

V for Vendetta (2005)

V for Vendetta gets so much right. Bleak, and full of backwards Tory-style patriotism, it’s V for Vendetta‘s casting that especially shines. Such a landmark in its own imagery and place in pop culture, the V/Guy Fawkes mask now has been totally adopted by global disrupters, Anonymous to represent their own anarchy for our internet driven lifestyles.

Talking about V for Vendetta to MTV, Moore said:

I’ve read the screenplay, so I know exactly what they’re doing with it, and I’m not going to be going to see it.

He elaborates:

Those words, “fascism” and “anarchy,” occur nowhere in the film. It’s been turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country. In my original story there had been a limited nuclear war, which had isolated Britain, caused a lot of chaos and a collapse of government, and a fascist totalitarian dictatorship had sprung up.

Now, in the film, you’ve got a sinister group of right-wing figures — not fascists, but you know that they’re bad guys — and what they have done is manufactured a bio-terror weapon in secret, so that they can fake a massive terrorist incident to get everybody on their side, so that they can pursue their right-wing agenda. It’s a thwarted and frustrated and perhaps largely impotent American liberal fantasy of someone with American liberal values [standing up] against a state run by neo-conservatives — which is not what “V for Vendetta” was about. It was about fascism, it was about anarchy, it was about [England]. The intent of the film is nothing like the intent of the book as I wrote it. And if the Wachowski [sisters] had felt moved to protest the way things were going in America, then wouldn’t it have been more direct to do what I’d done and set a risky political narrative sometime in the near future that was obviously talking about the things going on today?

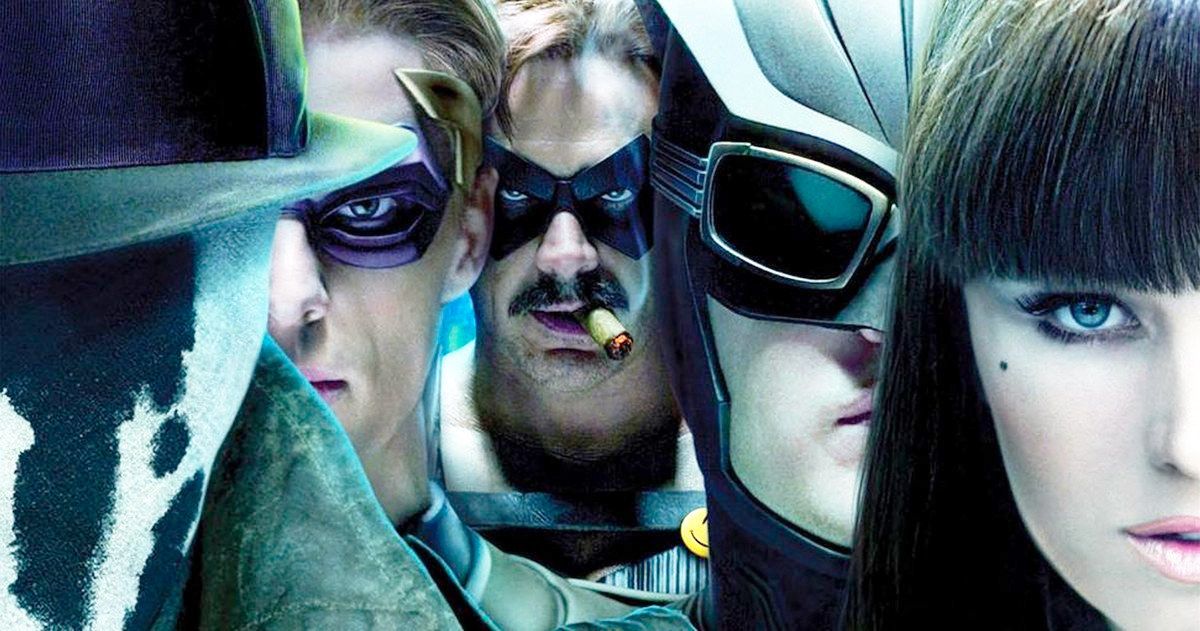

Watchmen Film (2009)

Before Zack Snyder became the poster child for sadboy DC superhero murk, he would show off in the overlong and bloated Watchmen. An extremely faithful adaption of the comic book (with like for like panels implanted to the screen), Watchmen has moments of sincere awe in its imagery but is dark and moody while lacking any heart at all. On the film adaption, Moore said in a Good Reads Q&A:

I not only did not approve of the attempts to adapt my work to a medium for which it was never intended, I have never seen any of these movies and hold them all in pretty much equal disregard. I would say that the Watchmen movie seemed to me particularly misguided, in that the only thing of any importance about Watchmen was its display of new storytelling techniques and potentials that were designed to be unique to the comic medium and almost impossible to any other.

It certainly wasn’t an attempt to reinvigorate a tired superhero genre. Quite the reverse: as with the previous Marvelman it was a critique of superheroes, and a meditation upon how these figures would look if they were disastrously transplanted to a realistically-depicted and above all adult world for which they’d never been designed. The opening page of Watchmen, with its impossibly long pull-back from a detail in a gutter to a position high above the street, was an up-front agenda-setting demonstration of something that could not be replicated in either literature or film, which is why I made it the book’s opening scene, and why I imagine the movie version apparently elected to leave it out.

Watchmen TV Series (2019)

Using Moore’s original comic book as a jumping off point, the Watchmen TV series felt much freer. Exploring themes of race and police brutality in a modern day America and its past, Watchmen quite literal world building would bubble up to a finale that was Must Watch TV.

In an interview with GQ most recently, Moore spoke of his experience in the build up to the show’s production and how he told creator Damon Lindelof never to contact him again:

[I received] a frank letter from the showrunner of the Watchmen television adaptation, which I hadn’t heard was a thing at that point. But the letter, I think it opened with, “Dear Mr. Moore, I am one of the bastards currently destroying Watchmen.” That wasn’t the best opener. It went on through a lot of, what seemed to me to be, neurotic rambling. “Can you at least tell us how to pronounce ‘Ozymandias’?” [Another of the vigilante characters in Watchmen.] I got back with a very abrupt and probably hostile reply telling him that I’d thought that Warner Brothers were aware that they, nor any of their employees, shouldn’t contact me again for any reason. I explained that I had disowned the work in question, and partly that was because the film industry and the comics industry seemed to have created things that had nothing to do with my work, but which would be associated with it in the public mind. I said, “Look, this is embarrassing to me. I don’t want anything to do with you or your show. Please don’t bother me again.

Unfortunately, he continues;

When I saw the television industry awards that the Watchmen television show had apparently won, I thought, “Oh, god, perhaps a large part of the public, this is what they think Watchmen was?” They think that it was a dark, gritty, dystopian superhero franchise that was something to do with white supremacism. Did they not understand Watchmen? Watchmen was nearly 40 years ago and was relatively simple in comparison with a lot of my later work. What are the chances that they broadly understood anything since? This tends to make me feel less than fond of those works. They mean a bit less in my heart.

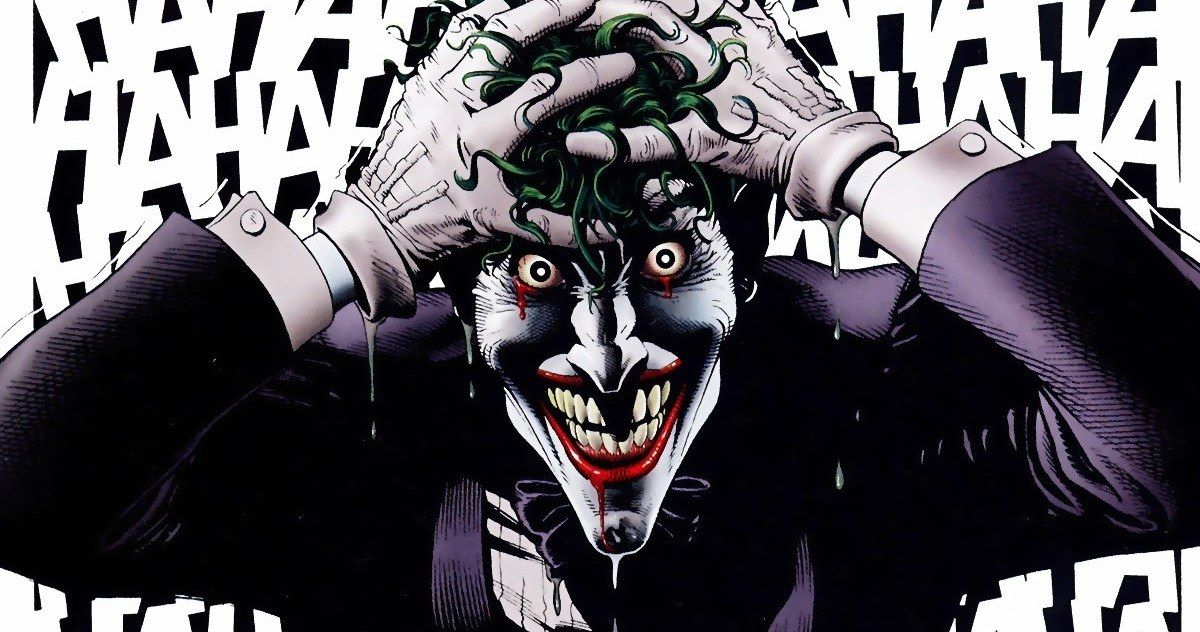

The Killing Joke (2016)

As one of the most well known and infamous Batman comics across the character’s entire run, the animated film adaption was met with a pretty poor response for its liberties (most notably expanding on the Batgirl character, and having her and Batman have sex on a rooftop ((in the comic she isn’t a superhero at all)).

Responding through the same Good Reads online Q&A, Moore stated:

As with all of the work which I do not own, I’m afraid that I have no interest in either the original book, or in the apparently forthcoming cartoon version which I heard about a week or two ago. I have asked for my name to be removed from it, and for any monies accruing from it to be sent to the artist, which is my standard position with all of this…material. Actually, with The Killing Joke, I have never really liked it much as a work – although I of course remember Brian Bolland’s art as being absolutely beautiful – simply because I thought it was far too violent and sexualised a treatment for a simplistic comic book character like Batman and a regrettable misstep on my part.