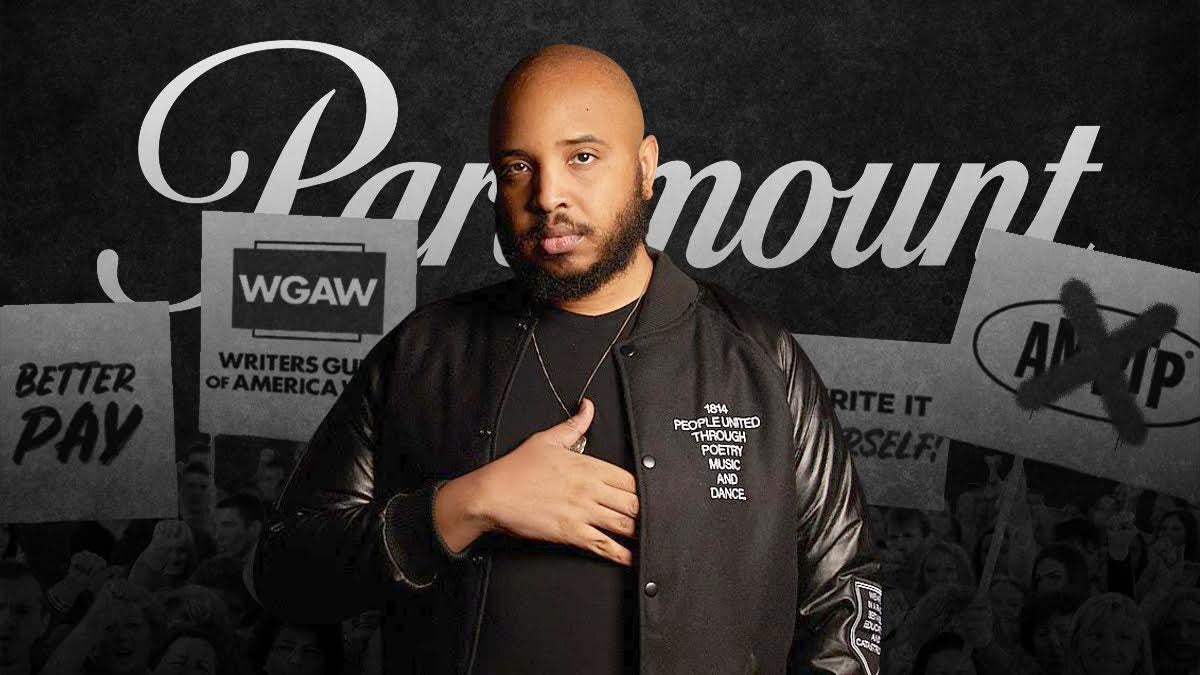

Culture Machine’s Justin Simien tells TheWrap that the strike has given studios an opportunity to cut costs at the expense of writers – a “very justified panic”.

Simien was “absolutely devastated and caught by surprise,” he told TheWrap about hearing the news in a call from his attorney on May 7. The letter that was sent to him was one of many.

The Writers Guild of America strike is entering its second month, and members like Simien are already feeling the financial crunch. A general concept in all types of commercial contracts, “force majeure” means an unexpected event beyond the control of either party. Brian Sullivan, an attorney at Earle Sullivan Wright Geyser & McRae, told TheWrap that in most Hollywood contracts, studios can enforce this in the event of a union strike. This often means no compensation under lucrative deals.

deals on hold

A suspension, like a simian, puts the deal on hold, extending the duration of the deal, regardless of how long the event is. But the clauses also often allow for outright cancellation after a certain period – something insiders see as a potential benefit to studios striking out, especially as they look to cut costs and focus on streaming content. Face the pressure of reducing your overall spending.

Simien said he knew the suspension was likely to go on strike. His company had just moved into its office after years of remote work during the pandemic. He said that going out for drinks to celebrate his birthday was the first time his team got together in person.

“The irony of that was wild,” he said. “But it felt really devastating and debilitating.”

A spokeswoman for Paramount TV Studios declined to comment.

The timing of the force majeure clause’s use usually depends on the specific language of the agreement signed between the studio and the writers. The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which is negotiating with the Writers Guild on behalf of the studios, declined to comment, as did the union. Guild website recommended Members consult with attorneys about specific contract language.

“Generally in the context of the entertainment industry a force majeure incident does not lead directly to termination. It’s usually a suspension,” Shalliz Sadig Romano, co-managing partner of Romano Law, explained to TheWrap. “If it goes on for a really long time, that contract can then stipulate that the production company or studio can terminate it. Can do.”

Romano stated that the reasons for the forced exercise could include “cutting the fat” for financial reasons, as well as major talent not being available to work a particular show after the strike was resolved. Studios may also seek to use production companies overseas unaffected by the strike.

“Certainly there was rumor on the street before the strike that this is an opportunity for these companies to purge themselves of really expensive deals,” Simien said. “We weren’t a very expensive deal so we took ourselves out of that category.”

Individuals with knowledge of the deals told TheWrap that the studio’s current suspension letters are primarily sent to writers who are not currently working on projects.

However, Simian said that the wave of letters he and colleagues received felt more “blanket” than what happened at the start of the 2007–2008 strike. In addition to Simien, “The Wire” creator David Simon revealed that his deal was suspended by HBO after 25 years of writing for the network. Simon found out when he was on the picket line.

“We were really just a week into the strike,” he said. “It sounds really cutthroat.”

He noted the studio facing financial pressures from Wall Street as a possible factor that could mean the suspension is coming to an end: “I think it’s a very justified panic that we’re all holding onto.” are and are preparing themselves for it.”

Simien said that he and the other suspended writers are in communication with each other and watch the first of each month for updates.

“I think we’re all acting like we’re all going to be eliminated, so let’s just be prepared for it,” he said.

little props for writers

Experts said that in the event of termination, the legal recourse for an author is limited.

“Theoretically, a writer could claim that certain producer services do not qualify as writing services and are compensated separately,” Sullivan said, adding, “The WGA has stated that all producer services by a member Writing is involved.”

One example where a writer might be able to find legal wiggle room is if an agreement with a studio doesn’t explicitly define force majeure as a strike, Romano said.

In that case an author could argue that “the strike is a foreseeable event, you saw it coming and you had no authority to enforce it and therefore you had no authority to terminate,” she said. But it depends on the details of the contract language.

tough decision

Simien believes that producers of color are at a particular disadvantage in this strike, as they accepted lower wages to produce their first shows, believing in the new opportunities promised by streaming.

“The minute there is profit, we are the first to get the axe,” he said. “We’re always the first to go.”

He insisted that the strike was “absolutely necessary because the things we are fighting for in the strike affect people of color more.”

“It’s not the Writers Guild’s fault,” he said. “The reason the strike is not ending is because the companies that can afford it are not giving the strikers what we are asking for.”

Simien received advice to either furlough or lay off his staff and cut all costs he could to ensure Culture Machine financially. Instead he reduced the wages of his employees: he could not stomach the idea of layoffs.

“Something in me just said I don’t want to do it this way,” he said. “I pride myself on producing teams from communities of color and queer people. I felt like I was doing everything I could to prevent a production company from doing what people of color and queer people do. It’s like turning my back on young people.

He worried that cutting his employees’ income might force him to leave the industry altogether. “I didn’t want it to be the first measure,” he said.

Several major TV/film studios are using the writer’s strike as grounds to abruptly suspend overall deals, leaving smaller production companies like Culture Machine and their employees in a sudden financial crunch – and nobody cares about it. I am not talking#wga #wgastrong pic.twitter.com/O5B8VRE3qh

— Culture Machine (@CultureMachine_) May 25, 2023

Instead, he launched a fundraising campaign on GoFundMe on May 23, which has since surpassed its goal of raising $60,000 to get the company through the end of summer. Any additional funds are being passed on to writers affected by the work stoppage.

Other producers with suspended deals are facing similar tough decisions, Simien said, but not everyone feels like they’re able to talk about it.

“There are people who are in a worse position than me,” he said. “And they don’t feel like they can really speak up about it because it’s not necessarily the ‘stars’ in Hollywood who have to work with that image to keep their business afloat.”

While Simien’s highly anticipated “Haunted Mansion” film is set to release next month, he said he is still in “triage mode” and is already looking at contingency plans in the event of an extended strike.

“No project, no matter how big on the outside, has really been a financial windfall to take care of the home and start a business,” he said. “I need that film to do well. I worked really hard on it. I’m really proud of it. And plus, my support staff has broken backs. So you can’t do those two things at the same time.” How do you balance that? I’m not sure.”

Simien hopes that when the dust finally settles, Hollywood’s business model for writers will be “fundamentally different” and changed for the better, as they have “more stories to tell”.

“I am definitely looking for a new model because it was not a good idea to start with the old model,” he said. ,[Studios have] Money and people and entry into industry, but my will to survive is too strong.

For all of TheWrap’s WGA strike coverage, click here.